Brief Commentary on “Harmony in Temporality: A Psychoanalytic, Scientific, and Pedagogical Inquiry into Surah Al-Asr in the Quran” by Reza Moezzi

My friend, a thinker with whom I share deep agreement on religion as a crucial and foundational framework for the functioning of both the individual and society in general, has published an interesting paper: “Harmony in Temporality: A Psychoanalytic, Scientific, and Pedagogical Inquiry into Surah Al-Asr in the Quran” (Quanta Research, ISSN: 2806-3279, Volume 2, Issue 2, DOI: https://doi.org/10.15157/qr.2024.2.2.44-54). As he has kindly asked for my brief opinion, I shall gladly share it.

Let it be noted that when it comes to the Quran, my knowledge is categorically more limited and superficial compared to my familiarity with the Bible. However, drawing upon overarching religious parallels and decades of work related to the psychological significance and practical value of religious thought, I feel confident in offering my insights.

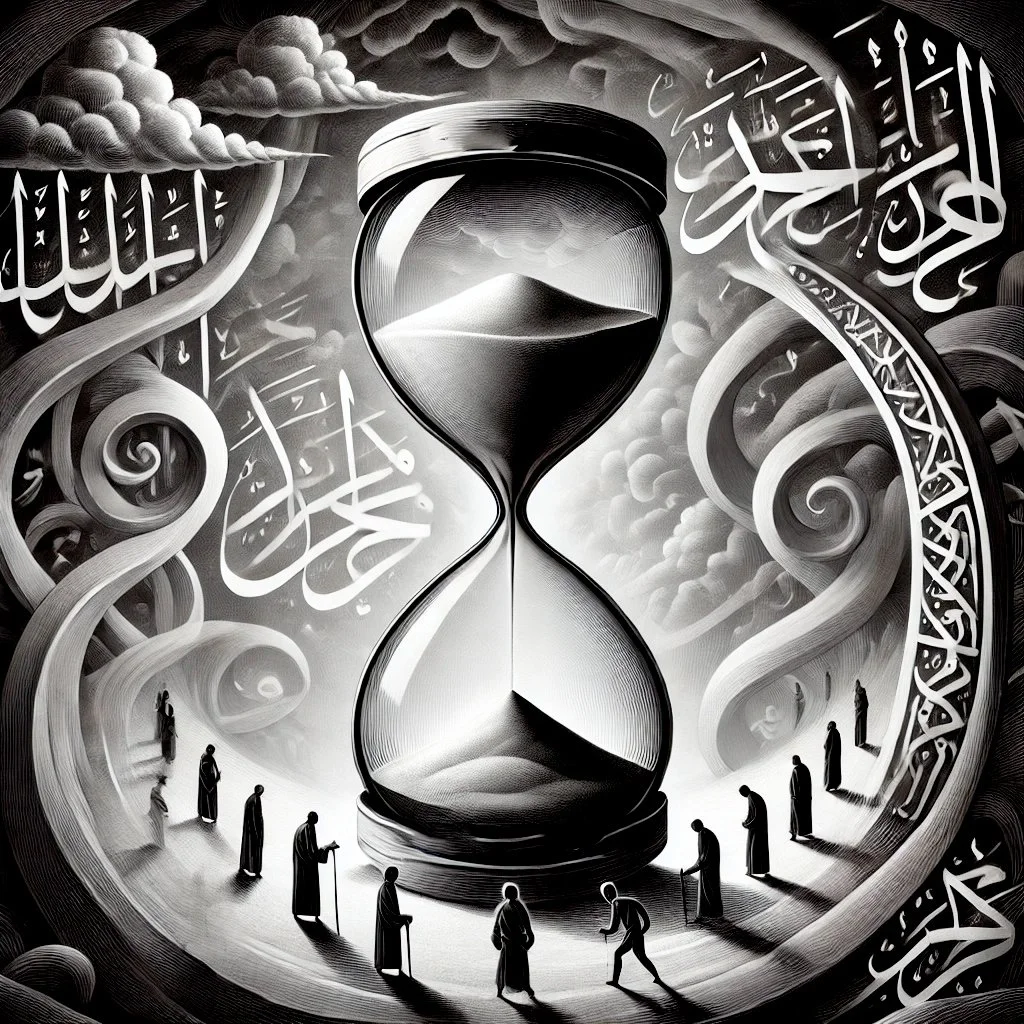

The text of Surah Al-Asr (103:1-3):

By Time [God swears by time]. Indeed, Man is in Loss, Except those who have Faith and do Righteous deeds, and enjoin one another to [follow] the Truth, and enjoin one another to Patience.

This is one of the shortest yet most profound chapters of the Quran. In terms of its density of thought, I would compare it to Genesis 4:1-16—where a similar concentration of meaning is presented in the form of a story. It addresses fundamental aspects of human existence and the conditions for an accurate and truthful being in the world. From a psychological perspective, I agree that these verses encapsulate key elements of human motivation, self-development, and resilience. Moreover, I believe that the most accurate framework for the psychological analysis of this verse is, quite evidently, existential, and thus dynamic. In this regard, I absolutely agree with the fundamental propositions posited by Reza.

Reza has divided the verse into three distinct symbolic instances:

“By Time” (1)

“Man is in Loss” (2)

“Except those who have Faith and do Righteous deeds, and enjoin one another to [follow] the Truth, and enjoin one another to Patience.” (3)

I fully agree with the first two divisions. However, I would argue that the third section contains two distinct thoughts, each of which is worthy of separate analysis. These should be treated as independent sections, namely:

“Except those who have Faith and do Righteous deeds and enjoin one another to [follow] the Truth.”

“And enjoin one another to Patience.”

In the following paragraphs, I will explain the rationale for this distinction.

As a side note, let me express my deep appreciation for Reza’s philosophical thought, intellectual curiosity, and way of thinking. Over the years — something this commentary clearly reflects — I have developed a tendency to posit absolutes in order to make my arguments as clear as possible. Thus, while I wholeheartedly agree with many of the ideas presented in Reza’s paper, I see them as instrumental in the final analysis of each section. Where there may appear to be a sense of opposition, it is, in reality, an alignment — one that I have taken the liberty of extending further (to the absolute).

First: "By Time (God swears by Time)"

For me, the swearing by time (Al-Asr) emphasizes its crucial role in human existence. Time is the most valuable and irreplaceable resource. From a psychological standpoint, awareness of time fosters self-regulation, goal-setting, and productivity. We, as human beings, possess the gift of being able to conceptualize temporality — in the simplest terms: we know that we are going to die. This awareness has given rise to various theoretical frameworks (Temporal Motivation Theory, etc.), which seek to harness temporality for effectiveness and purposeful living.

However, when analyzing temporality, I find it more compelling to adopt an existential framework—particularly one rooted in the concepts of existential anxiety, as articulated by Heidegger and Frankl. The awareness that time is finite defines our entire experience of being alive and serves as the foundation for seeking meaning in life.

Thus, this part of the verse most directly resonates with the concept of existential anxiety, a theme extensively examined by Heidegger and Viktor Frankl. The recognition that time is finite pushes individuals toward meaning-seeking behaviors. Regarding Reza’s paper, I agree with the two ways of conceptualizing time he presents. However, for me, that analysis serves as a stepping stone to understanding what this means for man (or, or as Dasein), and the conclusion I reach is existential anxiety.

I belive, Since God, as the speaker of these words, exists outside of time in His singularity, the ultimate purpose of this verse is not to present different measures of time, but to emphasize the existential burden that temporality imposes on man. In this regard, Kant’s notion of time as one of the a priori intuitions is particularly relevant. For me, time has always preceded and enabled space, making it an instrumental phase of analysis in arriving at the final meaning of this idea.

Second: "Indeed, Man is in Loss"

This statement, at least for me, presents a default psychological condition: human beings are in a constant state of decline unless they take active steps to counteract it. Once again, I agree with Reza’s (somewhat unnecessarily detailed) description of physical decline. However, I see that as instrumental rather than the definitive final idea. I would argue that there is always a natural tendency toward disorder and chaos — this applies not only to the physical world (and the human body) but, far more importantly, to human behavior (a conclusion that, I must admit, Reza reached—consciously or not). Without deliberate effort, people tend to drift into unhealthy habits, procrastination, instant gratification, and — most significantly — existential emptiness. Even CBT suggests that without structure and discipline, the mind naturally inclines toward negativity bias, rumination, and loss of direction.

In an existential sense, Sartre and Camus discuss the inherent absurdity of life and the inevitability of loss. However, this verse offers an antidote: a structured path to overcoming this existential crisis.

Matthew 6:33-34 states:

"But seek ye first the kingdom of God, and his righteousness; and all these things shall be added unto you. Take therefore no thought for the morrow: for the morrow shall take thought for the things of itself. Sufficient unto the day is the evil thereof."

This idea does not, by any means, signify a "Viva la Vida (Loca)" approach of merely living in the moment. Quite the opposite — it conveys the key principle that one must have a governing aim in life. Only then can one live in the present, focusing on daily worries and joys while maintaining a clear direction, anchored by a higher aim.

Thus, for me, this part of the verse underscores the necessity of centrality and monotheistic direction in life—a fundamental principle that religion provides. Being "in Loss" defines the idea that when the center is framed against the margin, the problem at the margin is not merely the lack of a singular, clear aim but rather the infinite possibilities for action (a point I will further elaborate on in the next section).

Third: "Except those who have Faith and do Righteous deeds and enjoin one another to [follow] the Truth”

Faith (Iman) signifies psychological resilience and serves as an antidote to chaos. It provides a framework for meaning, helping individuals cope with uncertainty, suffering, and existential dread. Faith grants direction, enabling one to pursue a higher purpose. Numerous studies on religious coping mechanisms demonstrate that faith reduces stress, increases emotional resilience, and fosters a sense of security.

There is no shortage of psychological research supporting the idea that taking action — engaging in meaningful and ethical behavior — enhances well-being. Self-Determination Theory (Deci & Ryan) suggests that humans require competence, relatedness, and autonomy to thrive—all of which are embedded in the concept of righteous deeds. Various scholars have explored this notion, yet once again, I aim for a higher level of analysis: the key question is not merely taking action, but rather — what action to take?

Here, I find Reza’s example of social media consumption particularly valuable as a symptomatic case of self-gratification and a lack of sacrificial will in human beings. This analogy makes it easier for readers less familiar with existential thought to grasp the broader point. Let us analyze this further.

The psychologically significant problem with instant gratification (e.g., social media overconsumption) is not merely the absence of discipline, sacrifice, and patience as virtuous behaviors. Rather, the true issue is the diabolical chaos of infinite, directionless choices. If an individual has willingly marginalized themselves and succumbs to instant gratification, this behavior is itself symptomatic of something deeper. Most importantly, those who fall into such habits often, at least partially and subconsciously, recognize a dark truth: no matter what they do next, none of it seems to carry any deeper significance.

We must acknowledge the grim underlying reality—the true driver of such behavior is, in fact, fear. More specifically, in the face of infinite possibilities, the problem is not simply that a given action (e.g., using a social media app) is incorrect, but rather that none of the available choices ultimately matter. Thus, for me, the key idea here is related to meaninglessness—the consequence of lacking a singular direction and an internal value hierarchy that establishes ultimate priorities. This, I believe, is also the key idea that unites both "the Loss" that man is doomed to and "those who have Faith and do Righteous deeds."

Regarding “Following the Truth

For me, this part of the verse is existentially related to ethical behavior — a way of living that aligns with deeper moral values. Truth (Haqq) in this verse represents both personal integrity and the broader concept of moral and intellectual responsibility. Such alignment is only possible by living in accordance with existential truth — the very truth that has enabled humanity to survive.

In other words, much like Kant’s categorical imperative, one must choose a way of life that minimizes unnecessary suffering and chaos for oneself, loved ones, and society in general. Psychological research also supports this. For example, Festinger’s theory of cognitive dissonance highlights the importance of cognitive consistency — living in alignment with truth reduces inner conflict, leading to mental clarity and stability.

I am convinced that one cannot simply declare their values through mere speech. The key idea here is behavioral — truth is not imposed through words but rather revealed through actions. One truly understands their values retroactively, through the deeds they have committed.

Encouraging truth among others aligns with several psychological theories. Bandura’s Social Learning Theory suggests that behaviors and values are reinforced through communal reinforcement. Similarly, ethical leadership — which we study at SelfFusion (www.selffusion.com) — and mentoring (both implied in "enjoining truth") are crucial for mental well-being. Helping others discover and adhere to truth strengthens our own sense of purpose and meaning.

Fourth: "And enjoin one another to Patience”

This phrase clearly (and, given my Christian background, unsurprisingly) signifies the importance of sacrifice — specifically, the ability to resist instant gratification, the power of emotional self-control, and the necessity of regulation and endurance.

Patience (Sabr) is not passive endurance but active perseverance in the face of adversity. This concept builds upon the previous sections: one can successfully sacrifice and deprive themselves only when they understand what they are sacrificing for. Without a higher aim, suffering becomes a meaningless burden. However, when a sacrifice is made with clear knowledge of its higher purpose, it not only justifies the suffering and makes it tolerable, but it also enables an overall patient and disciplined way of living.

There is no shortage of psychological research on resilience (Bonanno, 2004, etc.) showing that patience and long-term thinking are key indicators of success and mental strength. Delayed gratification, as demonstrated in the famous Stanford Marshmallow Experiment (which Reza references), correlates with greater self-control, higher success rates, and superior emotional regulation. CBT often emphasizes distress tolerance, which aligns directly with the Quranic principle of sabr. Encouraging patience in oneself and others fosters emotional strength and social cohesion.

However, while all of this is valuable, it remains insufficient for reaching the absolute. The absolute is simple:

Life, in its essence, is intolerably hard.

There is no shortage of tragedies that will strike from within (in the form of chronic illness and eventual death) and from without (through the suffering of loved ones, betrayal, unexpected and undeserved misfortunes, etc.). Much like Job, we will be put to the test. This is not some sort of pessimistic lamentation—it is an unavoidable truth. One must accept that such trials will come; it is not a question of something heppening, but rather the timing of the inevitable event. As my highly intelligent friend F.K. often remarked in various discussions: "It’s not a question of “if”, but “when”."

Thus, in this sense, "enjoin one another to Patience" (at least for me) signifies that the only way to live is by actively working to alleviate suffering — both for oneself, for those closest, and, ideally, for society as a whole. This is not a passive endurance but an active pursuit of meaningful and suffering-reducing behaviors, striving to make life better, bit by bit.

This has two sides:

Doing something genuinely good for others.

Eliminating behaviors that cause unnecessary pain, suffering, and harm to others.

Let us not deceive ourselves — the second must come first. Before one can improve life, one must first stop making it worse.

The Blueprint Surah Al-Asr Offers

The four elements outlined in this verse—and the four parts of my analysis—can be defined as faith, righteous action, truth, and patience. Together, they form an interconnected framework for living—a comprehensive psychological model that fosters human flourishing, both at the individual and societal levels.

I would define these principles as follows:

Existential Awareness

Recognizing the fleeting nature of time prevents complacency. Human beings are finite, and we are doomed to know it from a very early age. This awareness serves as the foundation for all meaningful action.Motivational Framework

Faith and righteous action provide purpose and structure, ensuring that one has a central aim in life rather than lingering at the margins, where "all is a question of interpretation." True meaning is not arbitrary—it guides and anchors.Ethical Integrity

Upholding truth ensures both psychological stability and social trust. One must resist the temptation to view everything as circumstantial or to become a "legion" of contradictory aims. Instead, one must cultivate singularity—aligning with something higher and unwavering. This includes appreciating dogmatic restrictions as necessary constraints to keep chaos in check. Freedom is not found in limitless options, but in knowing what is meaningful.Resilience and Grit

Patience fortifies the mind against hardships. Willful sacrifice is not just a virtue but a central strategy for coping with life, which—by its very nature—is tragic, painful, and unjust (life itself, not God, I must clarify for my atheist critics).

This Surah encapsulates a universal psychological principle: human beings require a structured moral and behavioral framework to counteract existential entropy and loss. By integrating these principles, one can cultivate mental resilience, purpose, and well-being in an ever-changing world.

Further Analysis: Surah Al-Asr as an Encapsulation of Yalom’s Four Existential Fears

As I know, Reza — much like myself — appreciates Irvin Yalom a great deal, and I believe we have both read all of his books (multiple times, as they are truly enjoyable). The only fundamental question I have for my friend Reza (half-jokingly) in this regard is: how did you not spot something so obvious?

Surah Al-Asr indeed encapsulates all four existential fears Yalom defined. Let me explain.

For those unfamiliar, the American existential psychiatrist Irvin D. Yalom identified four ultimate existential fears (or "givens") that define human psychological struggles:

Death

Freedom

Isolation

Meaninglessness

These fears represent fundamental anxieties that all humans must confront.

The four psychological principles I derived from Surah Al-Asr in my previous analysis—Existential Awareness, Motivational Framework, Ethical Integrity, and Resilience and Grit — serve as direct responses to these existential fears.

Below is a comparative framework that aligns the Quranic insights with Yalom’s existential psychology.

Existential Awareness – Fear of Death

"Recognizing the fleeting nature of time prevents complacency."

Yalom’s Fear of Death: The Inevitability of Mortality. Let me draw some psychological parallels: Death is the ultimate reality that humans struggle to accept. Many suffer from death anxiety, leading to avoidance behaviors, escapism, or existential paralysis.

Surah Al-Asr confronts this reality head-on by invoking time as a witness to human impermanence. Rather than being crippled by death anxiety, one is encouraged to use time meaningfully. This aligns with Heidegger’s concept of "Being-toward-death," which asserts that accepting mortality leads to authentic living—a subject I have explored extensively in my writings (williamparvet.com).

As we know, in psychology, Terror Management Theory (TMT) suggests that awareness of mortality can lead to either:

Fear-driven avoidance (denial, hedonism, or distraction), or

The pursuit of legacy and meaningful action (seeking significance, contributing to a cause, or leaving an impact).

I do not fully appreciate nor agree with TMT theory, but I mention it here as it supports this line of thought.

The Islamic response, much like existential psychotherapy, promotes acceptance of mortality—not through nihilism, but through constructive urgency, fostering a life of meaning.

In the simplest terms: Awareness of time and the inevitability of death should not lead to despair but to a meaningful engagement with life.

Motivational Framework – Fear of Meaninglessness

"Faith and righteous action provide purpose and structure."

Yalom’s Fear of Meaninglessness: The Anxiety That Life Lacks Inherent Meaning

The parallels here feel very clear to me. Existentialists like Sartre and Camus argue that life has no intrinsic meaning, and it is up to individuals to create their own. However, many struggle with this burden of meaning-creation, leading to existential emptiness, depression, or nihilism.

The Quranic model offers a structured response: Faith (Iman) and righteous action (Amal Salih) as a pathway to meaning. For me, this is, of course, closely related to Christianity, where the aim is as clear as it can be. However, the crucial idea is that there must be a rigid external structure that provides sufficiently dogmatic rules to anchor meaning and purpose.

Psychological research on eudaimonic well-being (i.e., meaning-driven happiness) suggests that people who have spiritual beliefs and ethical commitments experience greater life satisfaction and lower anxiety.

However, what I find even more significant is Viktor Frankl’s approach, which asserts that meaning is found through responsibility, values, and service to others—a perspective that, to my understanding, mirrors the Quranic emphasis on faith and righteous action.

In the simplest terms: Rather than treating meaninglessness as an insurmountable problem, one can actively engage in faith, ethical behavior, and purpose-driven living to find meaning — whether through Christianity, Islam, or any other solid framework (as I see no viable alternative outside of religious structures).

Ethical Integrity – Fear of Freedom (Responsibility)

"Upholding truth ensures psychological stability and social trust."

Yalom’s Fear of Freedom: The Anxiety That Comes with Radical Personal Responsibilit

The parallels here are striking. While freedom is often perceived as a positive, existentialists highlight that it also carries the burden of responsibility—we are fully accountable for our actions and choices. This concept also closely resonates with Reza’s description of instant gratification, where avoiding responsibility leads to self-indulgence rather than self-discipline.

Many people fear moral and existential responsibility, leading to:

Avoidance (refusing to confront difficult choices),

Bad faith (mauvaise foi in Sartrean terms—deceiving oneself to escape accountability), and

External blame-shifting (placing responsibility on external forces rather than oneself).

The Quranic principle of "enjoining truth" (Haqq) ensures that one does not evade responsibility but instead embraces moral clarity.

In psychological terms, Cognitive Dissonance Theory (Festinger) explains that people experience psychological distress when their actions contradict their values. Upholding truth eliminates this internal conflict, fostering inner peace and moral stability.

Furthermore, social trust is dependent on collective ethical integrity. Durkheim’s sociology emphasizes that shared moral frameworks prevent anomie (social breakdown due to a lack of norms).

However, for me, the more important psychological connection is with Jungian individuation — where self-actualization requires an honest confrontation with one's shadow and the acceptance of personal responsibility.

In the simplest terms: Freedom is not merely personal autonomy — it demands truthfulness, accountability, and ethical alignment to maintain psychological balance and social trust. Total freedom leads to chaos — without rules, it dissolves into orderless anxiety, which can ultimately lead to neurosis or psychosis.

Resilience and Grit – Fear of Isolation

"Patience fortifies the mind against hardships."

Yalom’s Fear of Isolation: The Fear That We Are Ultimately Alone in Our Suffering

Once again, the parallels are evident. Humans crave connection and support, yet everyone experiences personal suffering that cannot be fully shared. This existential isolation is often exacerbated by a lack of patience, as distress and loneliness can lead to despair and withdrawal.

The Quranic principle of "enjoining patience" (Sabr) is a direct response to this isolation — it encourages collective perseverance rather than solitary despair. From a psychological standpoint, research on resilience (Bonanno, 2004) demonstrates that grit and patience are essential for overcoming trauma and setbacks. Similarly, Attachment Theory (Bowlby) suggests that secure relationships are key to psychological health — those who endure hardships together strengthen their emotional resilience.

Furthermore, Bandura’s Social Learning Theory supports the idea that perseverance is contagious — when we promote patience in others, we simultaneously reinforce it within ourselves, fostering stronger communal bonds and support networks.

Taking It to the Absolute: A Christian Perspective

Let me now take this idea to its absolute and most “morbid” form.

From a Christian perspective, a lack of patience reveals an unwillingness to sacrifice — a prioritization of instant gratification over the well-being of family, loved ones, and society. This, in essence, is a true sin — one that prioritizes selfish whims over moral duty.

And the worse the sin, the harsher the punishment.

What, then, is the harshest punishment of all?

It is no coincidence that in Dante’s Inferno, the lowest level of Hell is not burning fire, nor physical torment, but a frozen abyss — where the worst sinners, trapped in ice, endure the purest form of suffering: isolation, immobility, and the loss of all meaningful connection.

In the simplest terms: Suffering is an individual experience, but when endured with moral purpose, it fosters resilience and strengthens the community as a whole. Inflicting unnecessary suffering on others results in moral degradation and existential isolation, as one distances themselves from rational humanity. Conversely, suffering together for a just cause reinforces shared duty and mutual respect. Thus, living in patience with others serves as a direct counter to Kant’s warning against treating people merely as means to an end, emphasizing the ethical necessity of recognizing each individual as an autonomous moral being.

Conclusion: A Psychological Blueprint for Existential Fulfillment

Surah Al-Asr is not just a theological doctrine—it is a psychological roadmap. It offers:

A proactive approach to death anxiety (Time-awareness and purposeful living),

A structured pathway to meaning (Faith and ethical action),

A moral anchor against existential paralysis (Truth and accountability),

A resilience-building mechanism against suffering and isolation (Patience, perseverance, and — let me add — sacrifice, as I am known for trying to “sneak in God”).

In this way, Islamic existential psychology aligns with and even expands upon Western existential thought, transforming existential dread into a cohesive and actionable life philosophy.

I sincerely hope this brief commentary, written at midnight in a hotel lobby while my children sleep in the room, serves as a token of my appreciation for Reza’s dedication to exploring deep existential topics and drawing connections that far exceed what many of us choose to spend our free time on. Is this not a manifestation of the four key ideas explored in this analysis and in Surah Al-Asr’s true logos?

Is not the very paper Reza wrote — one that provokes me and others to think and write — an act that makes life just a little bit better by aligning with a higher purpose?

I believe it is.