1. Introduction: In Search of True Subjectivity

In this introductory lecture, I usually begin with the principal observation regarding the division of the subject and present the fundamental idea that there is more than one "I." This self-evident concept runs through the “Romantics” and Kantian lectures, so we typically have a discussion with students about their previous experiences and, ideally, reach the conclusion that there are three levels of subjectivity (based on the evolutionary truth model).

The key to understanding the model of the Evolutionary Truth lies in accepting our limitations regarding understanding our primordial subjectivity. Who or what exactly is our subject, and where is it located? It is a principal ontological question that grounds many others that can arise in psychology, biology, and social ideology.

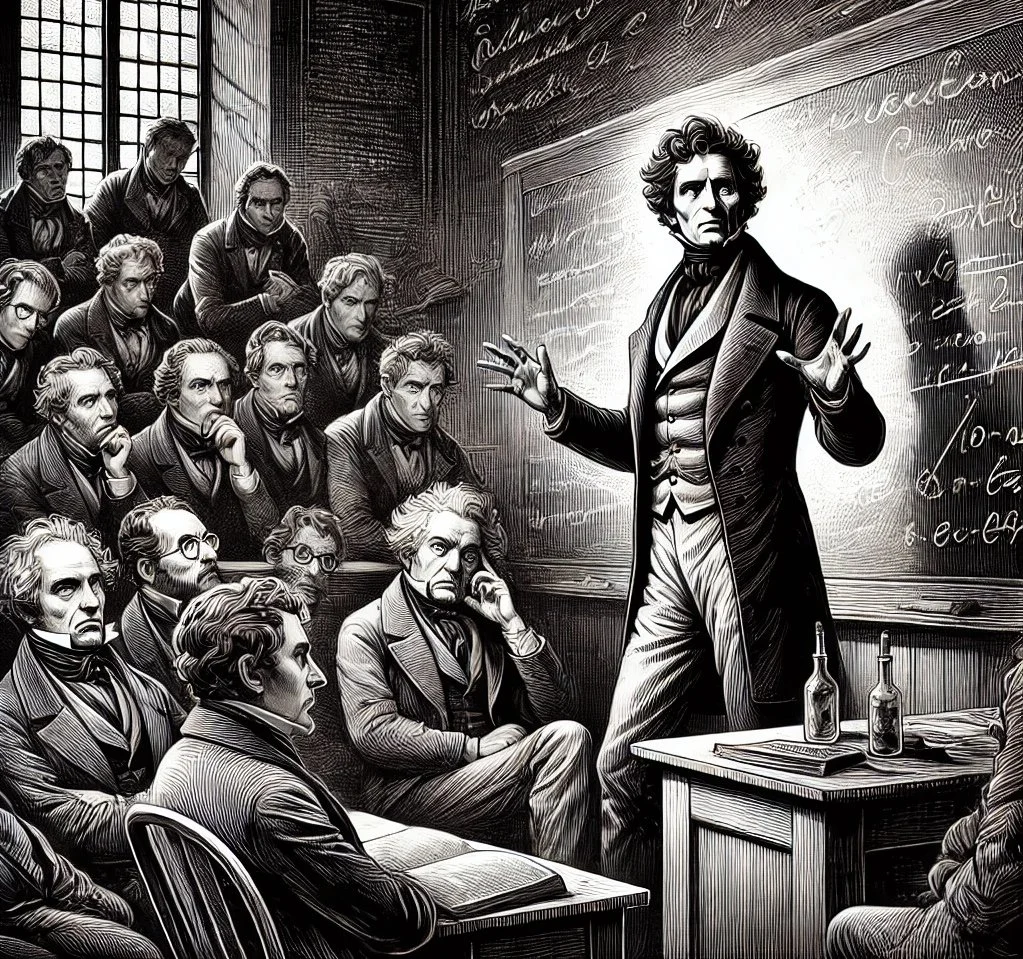

Fichte’s lecture The Question of True Subjectivity is nothing new and is phrased well in the story about Fichte. One of his students (Hendrik Steffens) recalls Fichte’s lecturing: “‘Gentlemen,’ he would say, ‘collect your thoughts and enter into yourselves. We are not at all concerned now with anything external, but only with ourselves.’ And, just as he requested, his listeners really seemed to be concentrating upon themselves. Some of them shifted their position and sat up straight, while others slumped with downcast eyes. But it was obvious that they were all waiting with great suspense for what was supposed to come next. Then Fichte would continue: 'Gentlemen, think about the wall.' And as I saw, they really did think about the wall, and everyone seemed able to do so with success. 'Have you thought about the wall?' Fichte would ask. 'Now, gentlemen, think about whoever it was that thought about the wall.' The obvious confusion and embarrassment provoked by this request was extraordinary. In fact, many of the listeners seemed quite unable to discover anywhere whoever it was that had thought about the wall. I now understood how young men who had stumbled in such a memorable manner over their first attempt at speculation might have fallen into a very dangerous frame of mind as a result of their further efforts in this direction. Fichte's delivery was excellent: precise and clear. I was completely swept away by the topic, and I had to admit that I had never before heard a lecture like that one.”

Fichte does not reveal the true "I" as the thinking subject here. Instead, he highlights the problem of duality between the "I" as the thinker and the "I" as an empirical construct that represents one's identity. In a later discussion, we will examine how Fichte attempted to resolve this issue in his philosophy. However, this thought experiment should help us understand that our perception of our empirical identity as an active subject in the world is distinct from the somewhat obscure entity that contemplates this subject.

We encounter the same set of dilemmas when composing our social media accounts. Can we claim that the "true self" of the person and the subject displayed in public are the same? Probably not. This situation is seen in the model of the Evolutionary Truth as the difference between the primordial subjectivity “S0” and one’s subjective representation “S1.” When we try to explore one’s true primordial self, we often (privately) think that it still has some hidden positive features and virtues that the public self, as our social identity, does not display and that others we encounter in life have to discover. Still, that way of thinking is often just a calm way to reconcile our inner duality, avoiding the core of the issue, namely the question: who precisely is analyzing our empirical identity? Giving it some thought should also lead us to an even greater dilemma: who is in charge of our subjective self? Where exactly is our true subjectivity located?

Those questions are more challenging than we often think because we are unlikely to possess the ability to encounter the “I” that constitutes our primordial identity.

“Cogito, ergo sum,” Descartes's famous statement, is a way to start exploring that duality. He states: “I am thinking, therefore I exist, which makes me sure that I am telling the truth, except that I can see very clearly that, in order to think, one has to exist.” Here Descartes was not defining the precise core of the subject with that statement, as he was focused on providing a foundation for indubitable knowledge.

He intrinsically connects the thought ("I am") to being ("I"), who exists and is thinking, and presents it as evidence of one's existence. He provides no concrete distinction about whether "I" as a subject appears first to create the thought ("I am" as an object) or if they emerge simultaneously. He states that thought is inseparable from him as an existing “thinking thing.” Thus, Descartes' statement is a logical argument for the existence of the “self” as “the doubter” or as the “thinking thing,” but it does not offer a specific explanation for the true nature of the self.

Kant’s dual (quadruple) subjectivity: If we wanted to explore what Descartes posited for defining the location of true subjectivity, we first have to take a step back when it comes to Kant. Namely, moving to define the “thinking subject,” we first have to secure its existence, and that is what mere “thinking,” as a process without content, does not allow us to do, per Kant.

Acknowledgment of “thinking” for Kant is just a reference to empirical intuition, the content of which is lacking (not to be confused with empty intuition, which just lacks an empirical object). The problem with the Cartesian approach is that “thinking” is a mere form of thought, without substantive matter ("Stoff") to apply this form to. One of Kant’s famous lines states that “thoughts without content are empty.”

Existence can be proven and deduced from the empirical intuition when we compose an object from perception, and for that, the categories of understanding and temporality (time as a form) are required. Kant explains that “only without any empirical representation, which provides the material for thinking, the act ‘I think’ would not take place.” Thus, he can also state: “Hence my existence also cannot be regarded as inferred from the proposition 'I think,' as Descartes held,” and adds that “thinking, taken in itself, is merely the logical function /…/ and in no way does it present the subject of consciousness as appearance.” As we can later see, that is also the reason why Fichte’s first principle was not just “A=A” but “I=I” (“Ich=Ich”), requiring one to form a thought that contains the thinker.

In the simplest terms, existence cannot simply be inferred from the proposition "I think," as Descartes held. For Kant, the existence of the thinking subject is grounded in empirical intuition; thus, thinking should always involve some content or representation derived from experience.

As a reader, one might now state that Kant’s opinion regarding the need for the content of Cartesian “thinking” does not help us find the location of our true subjectivity, which is a valid criticism. However, understanding Kant’s approach to forming cognition through combining intuition and concepts is also the key to understanding his approach to analyzing subjectivity.

Let us suppose “thinking” has content, and its content is a thought about oneself. It leads us to a situation where “I am thinking about myself thinking.” Now, we can deduce the “I”s of the “double I” (or rather the double consciousness of our “I”) in Kant’s approach. Let us examine it more closely.

According to Kant, when the thought has content (i.e., "me thinking"), there is cognition, which is a complete idea. This understanding arises from the combination of intuition (imagining oneself thinking) and concept (knowledge about what thinking is). This way, the obstacle of "empty thinking" is removed, allowing for the exploration of the "thinker."

When trying to find the “thinker,” we can see Kant building upon Descartes when it comes to the principle of synthesizing intuitions under the “I” that differentiates from the world (as “not-I”). He argues that, for any understanding to be reached, “I think” has to accompany the subject’s representations. This means that sensations must be gathered under one "I," which is only possible if the subject can represent himself as the thinking subject in a situation, similar to how Descartes described. However, for Kant, thoughts must have content, intuitions, and concepts to be considered valid cognitions.

When looking at the notion of the "I," Kant posits two levels of self-consciousness: an underlying consciousness that grounds intuitions and an empirical "I" that we can conceptualize as subjects in a situation (much like in the situation Fichte described in his lecture, and also how subjectivity is presented in the model of the Evolutionary Truth: “S0,” and “S1”).

Kant defines the “I”s of the “Double I” as: “1) the ‘I’ as subject of thinking (in logic) [the reflecting I], which means pure apperception,” and “2) the ‘I’ as object of perception [the I of apprehension], therefore of inner sense.” The "First I" represents pure self-consciousness, enabling the reception of sensations through our ability to sense time, space, and "built-in" concepts. The "Second I" is the empirical actor in the process.

At that moment, we can reach (as Kant did) a fascinating conclusion regarding the true subjectivity of our consciousness—namely, what we ordinarily consider to be the subject in a situation (“I” as an empirical actor, doing something, i.e., “thinking about the wall”) is not our actual subject but an object of the transcendental thinking subject that thinks about us doing something (thinks about us thinking about the wall). This implies that our perception of ourselves as our identity and as an actor in a situation is merely the representation in the form of thought (object) of our primordial consciousness as true subjectivity. Consequently, any conclusions we make about our true subjectivity can only be presumptions based on the results of its thinking. As Kant states, "The I of inner sense, that is, of the perception and observation of oneself, is not the subject of judgment, but an object." Thus, we can analyze only the traces of true subjectivity, while its essence remains unknown to us.

Kant says that whatever we do, the best we can achieve is to analyze the appearance as “he appears to himself, not as he, the observed, is in himself,” not our essence as a thing in itself (“not the inner characteristic of the subject as object [of examination]”). In the Critique of Pure Reason, he admits: “Through this I, or He, or It (the thing), which thinks [‘I of the pure apperception’], nothing further is represented than a transcendental subject of thoughts.”

Here we can say that Kant recognized the problem of determining the locus of consciousness and the fact that we live our everyday lives referencing ourselves without identification (something that was described around 200 years later by Sydney Shoemaker). When we do try to make a reference, we tend to take our thoughts for being the subject or, as Kant put it, “nothing is more natural and seductive than the illusion of taking the unity in the synthesis of thoughts for a perceived unity in the subject of these thoughts.” In short, Kant understood and seemed to refer to the concept of “self-reference without identification” (a term used later by Shoemaker) as us tending to refer to oneself without necessarily identifying oneself as a distinct object, often recognizing ourselves through (or as) our thoughts, calling it “hypostatized consciousness (apperceptionis substantiae).”

Analyzing our pure apperception, or primordial consciousness, can also be seen as paradoxical, similar to Russell's paradox in mathematics. This paradox arises when we try to classify our thoughts and their relationship to our consciousness.

Consider that we are an entity in the world, distinct from mere thoughts. In this case, we can identify a set of thoughts separate from ourselves ("my thoughts" as not-me). When thinking about objects in the world, these thoughts can be sorted into the set of "my thoughts" (not-me). The situation becomes problematic when we contemplate our primordial subjectivity or pure apperception (consciousness).

If the concept of my pure consciousness belongs to the set "my thoughts" (not me), then it must be a set that does not contain me. This leads to a contradiction, as it implies that "my thoughts" both include and exclude myself (as my pure consciousness). On the other hand, if my pure consciousness is not a member of the set of my thoughts, then it must be a set that contains itself. This also results in a contradiction, as it suggests that the set "my thoughts" both contains and does not contain itself (since I am the one doing the thinking).

Realizing the problem of self-analysis through Russell’s paradox perspective gives us the logical binding; the practical paradox is related to how our mind combines intuition with concepts to build cognition. Let us explore that briefly.

According to Kant, the subject perceived through the inner sense can only be represented as appearance, not as a stable, fixed entity of our noumenal self. This appearance is something we perceive and experience in time. However, the moment this perception becomes available for synthesis and analysis, it's no longer the (atemporal) thing in itself.

Furthermore, active introspection transforms our perception of ourselves, generating a new manifold of self-appearance that we experience in time, akin to how we experience other objects. This process presents a challenge: we cannot intellectually analyze our true subjectivity as something stable, permanent, and real. Each time we engage with an appearance for exploration, a potentially new manifold of temporal appearance emerges, and we start perceiving and synthesizing it into an understandable cognition. Consequently, we might gain insights into who or what we are, but these cognitions lack certainty—they merely represent a potentially unstable manifestation of noumena.

Therefore, synthetic a priori judgments about our true subjectivity are unattainable (it is impossible to know if those correspond to the truth). This perspective contrasts with Descartes' simplification that we can know ourselves (and our existence) prior to experiencing ourselves in time—a simplification that Kant fundamentally rejects.

Kant recognizes the paradoxical nature of the relationship between the empirical "I," which is a manifold, and the noumenal pure apperception that allows it to exist. He understands that the pure apperception is a simple thought, a condition for synthesizing intuitions. Kant acknowledges that both "I"s must be "identical with each other as the same subject." Yet, he grapples with the question of how the thinking subject can cognize itself as an object or, more directly, "how one can be an object of inner perception for oneself."

That duality fits in the model of the Evolutionary Truth. However, to justify the subtitle of this section, let us celebrate the multifunctionality and depth of the primordial subjectivity some more. When interpreting Kant, it is possible to define the "third" and "fourth" self. The "transcendental ego," or the unity of subjectivity in experience (referred to by Kant as the "transcendental unity of apperception"), can be considered the "third self." Meanwhile, the "moral self," which becomes significant regarding practical reason in Kant's moral philosophy, could be seen as the "fourth self." Just as I thought I might have discovered some originality in developing the idea of "quadruple subjectivity" with the third and fourth selves as constructs of primordial subjectivity, I stumbled upon a captivating description of the same concept by an excellent Kant scholar and an all-in-all fabulous character, Robert Paul Wolff. Written over forty years prior, Wolff explains this idea exceptionally, presenting a compelling case for the possibility of the "transcendental ego" having a real function as a "third self" to our experience of ourselves and others in the world. This interesting discussion we shall continue in the next chapter.

In the simplest terms, Kant acknowledges that the actual pure primordial consciousness (apperception) that has agency is the source of our thinking, and our empirical consciousness is an object of its thought. However, we cannot make any definite conclusions about our pure apperception, except that its essence remains unknown to us.