5. Fifth Lecture: The “Fourth Self” and Argument for the Moral Law

This lecture is, in a way, an extension and also an explanation of the previous lecture. After the dust of the debate has settled, I offer my own take on how to reconcile the "irreconcilable" and explain how I can justify Kant. Many scholars have criticized me for going to great lengths to defend Kant (especially, but not only, against Hegel); however, I stand behind my words. We also discuss my short observation of "Kant as a startupper," which illustrates the way I have been able to reconcile this for myself. Much homage is paid to Wolff, who has helped me reach these conclusions.

Exploring Kant's moral philosophy allows us to introduce the concept of the "fourth self"—the moral guide and considerate overseer of our empirical self as it negotiates the world of sensation and feeling. This concept is reminiscent of Freud's dichotomy of the unconscious and conscious ego. Freud suggested that our unconscious ego is “seeking to avoid the unpleasure which would be produced by the liberation of the repressed,” while our conscious ego aims to achieve tolerance of this discomfort ("procuring the toleration of that unpleasure") through adherence to the reality principle. In a similar vein, Kant's moral self operates as an overseer of the empirical self.

Central to Kant's moral philosophy is the ability of the "moral self"—a construct of our noumenal self—to disrupt the causal chains of life events. By synthesizing representations through an a priori moral rule determined by reason, the moral self guides us toward moral behavior. As per Kant, “regardless of the entire course of life he [one] has led up to that point,” if the transcendental self chooses to intervene at the moment of action, it takes precedence over our mundane drives. In essence, we possess the capacity for moral freedom.

In the simplest terms, Kant’s moral self can be seen as the “fourth self,” enabling us to make moral choices regardless of our past experiences or circumstances.

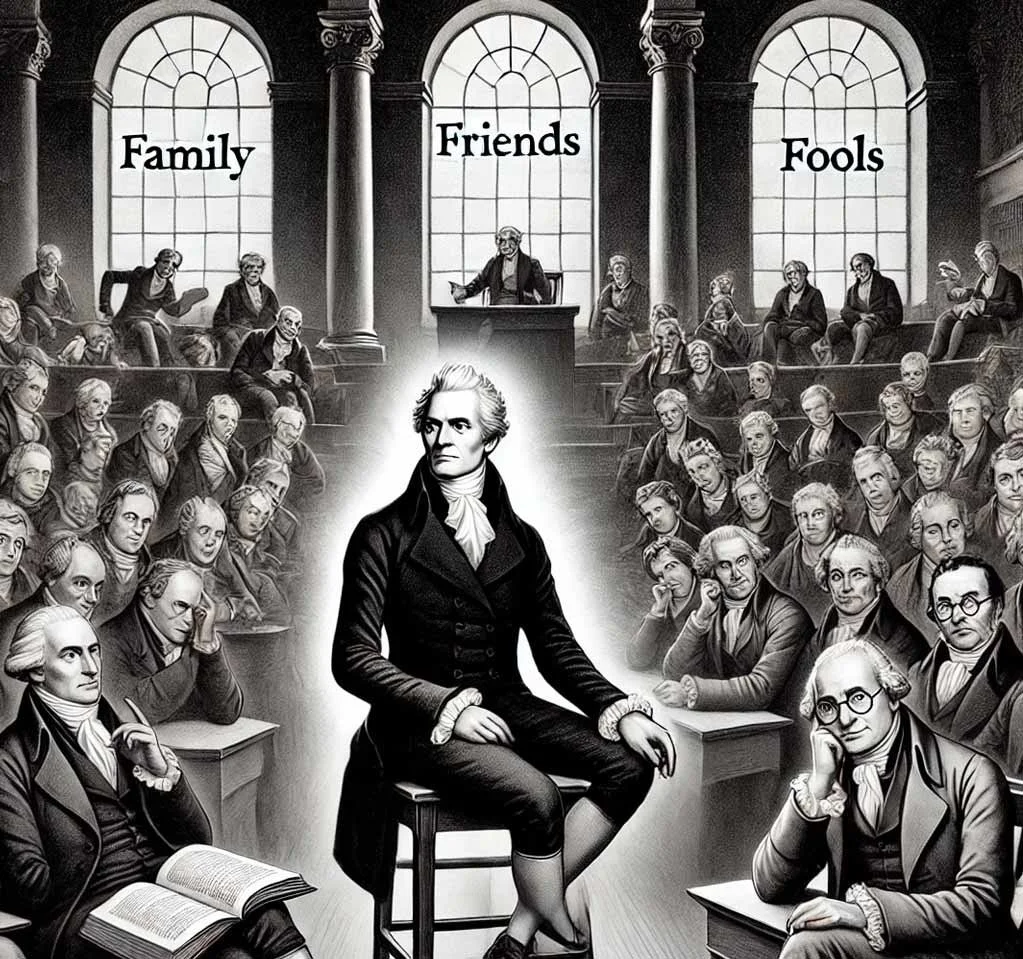

Kant as a “startupper” pitching the “three F’s”

Here, I feel obliged to draw attention, just a little bit, to the connection and overlapping structure of the argument of causality in the Critique of Pure Reason and Kant’s moral philosophy (especially in the Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals). Once again, I have to recognize Wolff’s clarity when it comes to describing the structural similarities (in fact, a rather remarkable synchronicity) of Kant's arguments in those two books. In his commentary on the latter, Wolff presents Kant as a good startupper approaching the traditional three F’s (family, friends, and fools) with slightly different pitches, yet selling the same idea (those three audiences are targeted in three chapters respectively).

In the first chapter, Kant turns to “family,” an audience that would accept and approve of his argument with a loving glance, no matter what. For them, Kant states the argument presupposing that there are shared moral convictions (that we have inherently accepted already as the truth). Namely, he says, "if those universal and innate moral arguments are true, then the Moral Law is self-evidently binding to all of us." That argument mirrors the first approach in the Critique, where Kant deduces the existence of categories from the realization that we have a priori knowledge of mathematics.

The second audience, which we can refer to as “friends,” are a bit more critical, and thus Kant shifts from slow cruising to second gear. His argument in the second chapter is binding: if pure reason can be practical in the sense of causing me to behave in a certain way, then the only valid law for such a motivating reason is the Moral Law. With that approach, he annuls the possible counterargument (if my pure reason is not practical, then I could never be condemned for any of my actions, as I have no control over them). Thus, the Moral Law has to be accepted as true, or all humans are deemed to have no freedom at all. The corresponding second level of the argument in the Critique is the following: if we have experience of the world of objects and can distinguish between our subjective understanding and the objective order of the world (meaning that we recognize our transcendental self applying a priori rules to the world that can contradict our subjective intuitions and their order in time), then mathematics and physics are valid.

The third audience, “the fools,” are the outside investors who can be questioning and disagreeable. With them, Kant (in both books) goes all in, putting the skeptic in a position where, by merely opposing, they would refute themselves and prove Kant right (or alternatively choosing not to oppose, thereby presenting Kant the victory by surrendering and walking away in silence). In the third chapter of the Groundwork, he states the argument for us being bound by the Moral Law the following way: “if a man is capable of taking action at all (pure reason can be practical), then it must also be possible that pure reason can make him act.” With that, he unarms any opposition because, in case an argument is made (an action), initiated by pure reason, the opponent already proves Kant right. In the Critique, the similar “all-in-to-the-max” version of the argument states: “If I am conscious (able to attach ‘I think’ to a representation), then mathematics and physics are valid.” All opponents are silenced because any counterargument would mean attaching “I think” to those, thus proving the existence of self-consciousness and, by that, proving Kant right. That is how Kant rolls.

In the simplest terms, a clear connection can be found between Kant's moral and theoretical philosophy. He can be seen as a "startupper" approaching different audiences with slightly altered pitches, making the same argument.